"One Cat" or "A Cat"? Why Chinese Measure Words Drive Learners Crazy (And Why They Actually Make Sense)

"One Cat" or "A Cat"? Why Chinese Measure Words Drive Learners Crazy (And Why They Actually Make Sense)

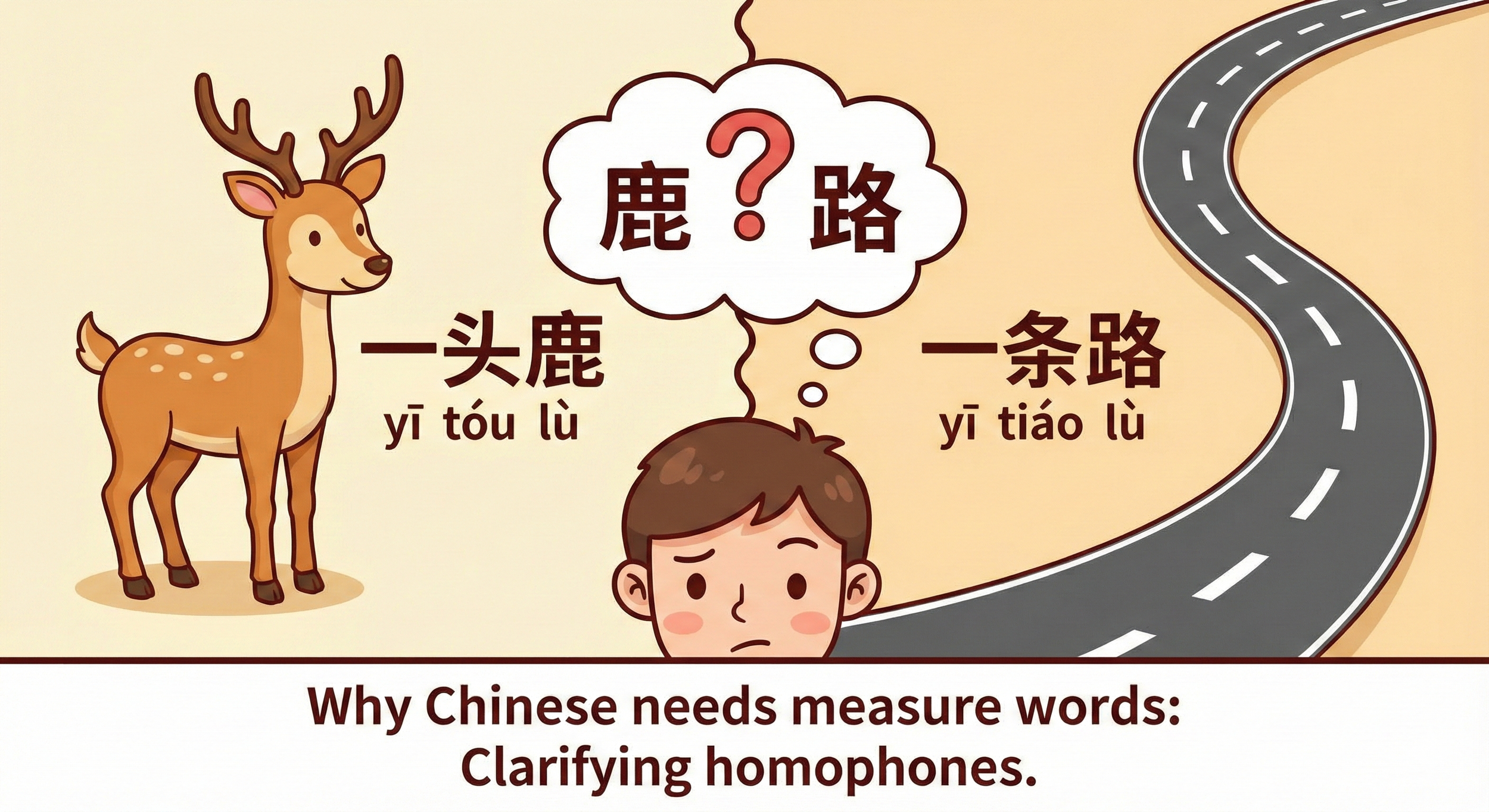

In English, "deer" and "road" sound very different. In Chinese, they can sound the same. So speakers added extra sounds to words to avoid confusion.

"Give me an apple." (Gěi wǒ yī gè píngguǒ)

"I'd like a milk tea." (Lái bēi nǎichá)

"That cat is so cute." (Nà zhī māo hǎo kě'ài)

If you are learning Chinese, these phrases are probably part of your daily survival kit. But have you ever stopped to wonder: Why?

In English, you say "a cat." In Chinese, if you say "yī māo" (one cat), people will look at you strangely. You must say "yī zhī māo" (one [unit of] cat).

For many learners, these measure words (quantifiers) feel like "drawing legs on a snake" (画蛇添足)—an idiom meaning unnecessary effort. They seem like useless hurdles designed to give foreigners a headache.

But here is the truth: Measure words aren't just random grammar rules. They act as a secret code to unlock the logic, history, and beauty of the Chinese language.

Let’s dive into the fascinating reasons why Chinese evolved to need these "useless" words.

1. The Survival Instinct: Solving the "Homophone" Crisis

The primary reason for measuring words isn't grammar, but rather audio clarity.

In written Classical Chinese, characters are distinct. But spoken Chinese has a limited number of sounds (syllables). English has thousands of distinct syllable combinations, but Mandarin (ignoring tones) has only about 400. Even with tones, it’s around 1,300.

This leads to a massive amount of homophones (words that sound exactly the same).

The "Deer vs. Road" Dilemma

Imagine you are hiking with a Chinese friend. You see something and shout: "Look! Lù!"

Your friend is confused. What did you say?

Lù (鹿)? - A Deer?

Lù (路)? - A Road?

Lù (鹭)? - A Heron?

Lù (露)? - Dew?

In English, "Deer" and "Road" sound nothing alike. In Chinese, they are identical. To fix this, the language evolved to add "padding" to words to prevent misunderstandings.

If you add a measure word, the ambiguity vanishes immediately:

"Yī tóu lù" (One head of lù) = It must be an animal, likely a Deer.

"Yī tiáo lù" (One strip of lù) = It must be long and thin, likely a Road.

The Takeaway: Measure words categorize nouns. They act as a "redundancy check" to help your listener figure out which "Lù" you are talking about before you even finish the sentence.

2. The "Error Correction" Mechanism

Spoken language is messy. There is background noise, people mumble, or they speak too fast.

In European languages like French or Spanish, nouns have Gender (masculine/feminine). Learners often complain, "Why does a table need to be feminine?" But functionally, gender helps listeners track which adjective belongs to which noun in a long sentence.

Chinese measure words serve a similar function. They provide Listening Tolerance.

If you are in a noisy market and miss the noun, the measure word gives you a clue. If you hear "... běn ..." (the measure word for books), even if you didn't hear the word "book," you know the topic is likely a book, a magazine, or a passport.

3. It's Not Just Grammar, It's "Attitude."

This is where Chinese gets poetic. Measure words don't just count things; they describe relationships, shapes, and feelings.

The Hierarchy of Respect

Compare these two phrases for "a teacher":

Yī gè lǎoshī (一个老师): Grammatically correct, but casual.

Yī wèi lǎoshī (一位老师): The measure word wèi implies a position of honor.

Using the wrong one doesn't make you "wrong," but it changes the social temperature. Using gè feels neutral or flat; using wèi shows you have manners.

The Emotional Distance

Yī zhǐ māo (一只猫): A cat (implies a small, cute animal).

Yī tiáo māo (一条猫): A cat (implies a long shape, perhaps seeing a stray cat slinking away in the distance).

The choice of measure word paints a picture of how the speaker views the object. It adds "human temperature" to cold data.

4. The "Lazy" Trend: Is "Gè" Taking Over?

You might notice that younger Chinese speakers invoke the "Universal Gè" rule.

In casual, rapid speech, "gè" (个) is swallowing up other measure words. You will hear yī gè píngguǒ (an apple), yī gè lǎoshī (a teacher), and even yī gè xīngqī (a week).

Does this mean measure words are dying?

Not exactly. While the semantic meaning (describing the shape) is fading in casual chat, the pragmatic function (showing tone and respect) is getting stronger.

If you use "gè" for everything, you will be understood, but you might sound like a robot—or a child. To sound sophisticated, poetic, or respectful, you still need the full arsenal of measure words.

📝 Key Takeaways (划重点)

If you are feeling overwhelmed by measure words, remember this summary:

They are Safety Goggles: Their primary job is to fix the "Homophone Problem." They distinguish "Deer" (tóu) from "Road" (tiáo) when the sound (lù) is identical.

They are Audio Buffers: They add rhythm and redundancy, making it easier to understand spoken Chinese in noisy environments.

They Carry "Vibes": They aren't meaningless. Wèi shows respect; kǒu (for family members) shows intimacy. They tell you how the speaker feels about the object.

Don't Panic: In a pinch, "Gè" works 90% of the time for beginners. But to master the "soul" of Chinese, learning the specific measure words is the secret key.

| Measure Word | The Secret Logic / Imagery | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1. 只 (zhī) | Small Animals & Single Parts. Used for small creatures or one part of a pair. | 一只猫 (a cat), 一只鸟 (a bird), 一只手 (one hand) |

| 2. 条 (tiáo) | Long, Thin & Flexible. Think of things that flow like a river or bend like a branch. | 一条鱼 (a fish), 一条路 (a road), 一条裤子 (pants) |

| 3. 张 (zhāng) | Flat Surfaces. Things that can be "spread out" or have a flat face. | 一张纸 (paper), 一张桌子 (a table), 一张床 (a bed) |

| 4. 位 (wèi) | Polite Status. Used for people when you want to show respect (better than "gè"). | 一位老师 (a teacher), 一位客人 (a guest), 一位医生 (a doctor) |

| 5. 本 (běn) | Bound Items. Things that have a spine or are bound together like a volume. | 一本书 (a book), 一本杂志 (a magazine), 一本护照 (a passport) |

| 6. 件 (jiàn) | Items & Matters. Often for upper-body clothing, or abstract "matters" to attend to. | 一件衬衫 (a shirt), 一件行李 (luggage), 一件事 (one matter) |

| 7. 双 (shuāng) | Natural Pairs. Things that almost always come in twos. | 一双鞋 (shoes), 一双筷子 (chopsticks), 一双眼睛 (eyes) |

| 8. 把 (bǎ) | Things with Handles. Objects you can grasp with your hand. | 一把雨伞 (an umbrella), 一把椅子 (a chair), 一把刀 (a knife) |

| 9. 辆 (liàng) | Wheeled Vehicles. Anything with wheels used for transport. | 一辆车 (a car), 一辆自行车 (a bike), 一辆公交车 (a bus) |

| 10. 块 (kuài) | Chunks & Pieces. Irregular pieces of a whole, or solid lumps. | 一块蛋糕 (cake), 一块石头 (stone), 一块钱 (one Yuan) |